#movingcity - City logistics: towards a sustainable equilibrium

The challenge: rapid rise, uncertain future

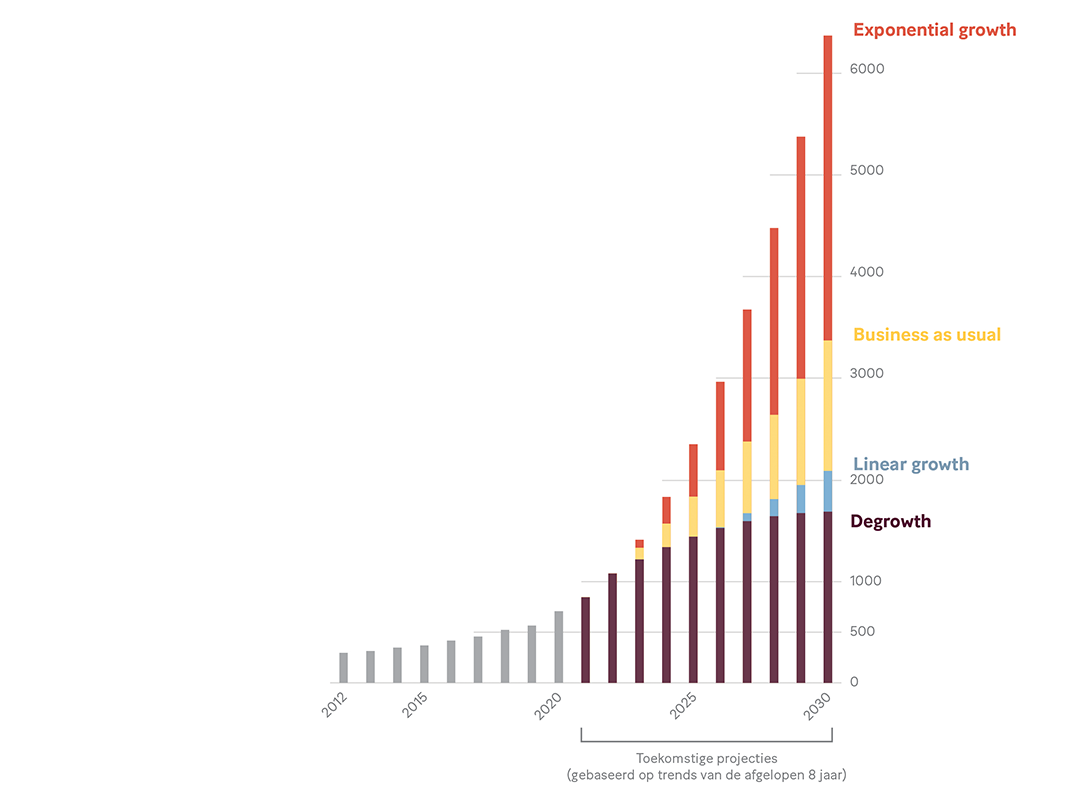

The number of logistics trips has grown sharply in the past eight years. More and more of these involve just-in-time deliveries to homes and shops, with products supplied as they’re needed. Flash delivery is a conspicuous and much-talked-about example. Since they first appeared in the Netherlands in late 2020, their popularity has soared. Use of these services doubled in the second half of 2021. Superfast delivery is especially popular in the four biggest Dutch cities, particularly among residents in the 18-to-34 age category, with 6.9% getting their groceries this way. It’s widely known among urbanites in general: 80% of city residents are familiar with the concept.

This familiarity may have to do with the fact that this form of logistics is literally claiming its place on the streets. Cyclists and scooter riders with striking uniforms and giant bags zigzag through traffic to deliver the goods on time. And so-called dark stores are appearing in more and more areas. Flash delivery drivers can often be seen queueing up outside these mini-depots with their blacked-out windows, waiting for the next trip. On the streets, suppliers impede traffic flows. Traffic and noise problems are also worsening in tandem with the popularity of courier delivery. More and more cities are taking steps in response. The City of Amsterdam called an immediate halt to new flash delivery hubs in late January, and Rotterdam followed suit a few weeks later. Other cities are doing the same, often following complaints.

To combat the environmental effects of city logistics overall, more and more cities are creating emissions-free zones to limit CO2 impact. Only electric vehicles are permitted in these zones. Goods are transferred from big fuel-burning lorries to larger numbers of smaller, clean vehicles on the fringes of the city. This system requires new peripheral transshipment points, creating a spatial planning task. Meanwhile, the growth of city logistics overall is taking up space needed by other traffic at street level, and to ensure livability and sustainability at city level.

Developments in city logistics are taking place in rapid succession: new vehicles are coming on the scene, flash delivery companies are cropping up and being banished, and new legislation is forcing mobility to get cleaner. It’s impossible to tell exactly which direction things are heading in. But we do know that spatial developments always run behind, because the physical city changes at a much slower rate. The conflict between these different paces of development is forcing us to think farther ahead and more broadly. What will city logistics look like in 20 years?

The solution: four possible future directions

To find a well-grounded answer to that question, we conducted research to determine potential future city logistics scenarios. Extrapolating from trends, we outlined four such scenarios, based on a matrix with two variables: how integrated or segregated the logistics system is and whether urban planning is more focused on quality of life or logistics. In each case, we looked at the implications for transport types, infrastructure and hubs (transshipment points between different logistics streams).

Scenario 1: Integrated logistics system within city-focused urban planning

In an integrated system, various logistics streams are combined to maximise efficiency. For example, couriers may also pick up customers’ returns and deliver them elsewhere. The spatial impact on logistics traffic is minimised, and room is freed up for attractive, cyclist- and pedestrian-friendly outdoor space.

Multiple services are combined in a small number of large hubs – clusters of shops, pick-up points, catering businesses and other facilities. Grouping services at hubs comes at a cost to small businesses.

Scenario 2: Integrated logistics system within logistics-focused urban planning

Neighbourhoods are designed as integrated logistics machines. Home deliveries are made from clustered hubs using small autonomous forms of transport. Logistics streams can be optimised with new technologies such as drones and underground transport.

Clustered logistics facilities eliminate a significant number of shops and services from the streets. A more efficient use of space makes it possible to develop housing at street level, for example.

Scenario 3: Segregated logistics system within city-focused urban planning

In this system, different services handle their own logistics; this is mainly more efficient for their own operations. This system results in a larger number of smaller vehicles on the roads and hubs that handle smaller volumes. Restocking and deliveries take place at night, minimising nuisance.

The city’s streets contain a wide variety of shops and services. The relative calm in daytime means public space can be designed around slow traffic, greenery, and pleasant places to linger.

Scenario 4: Segregated logistics system within logistics-focused urban planning

Separate logistics streams are given as much room as possible in this scenario. Thus, logistics dominates outdoor space. Features such as priority lanes for restocking and home delivery ensure maximum availability and speedy service.

An extensive system of dark stores in the neighbourhood makes this system possible, at the expense of local services. These stores differ in volume and function but exist for the same purpose: facilitating instant deliveries.

Conclusion

The more cities densify, and the greater the need for changes around sustainability and livability becomes, the more of a problem the availability of services and products will be. The four future scenarios point the way towards possible solutions by showing how logistics systems relate to spatial design in the city. It is clear that integrating different logistics services can reduce the number of transport movements. And the accessibility of logistics hubs affects the liveliness of city streets. But most of all, what’s becoming clear is this: we can’t do everything everywhere at the same time. Which streets do we want to be lively and pleasant, and where would we rather sacrifice spatial quality for logistics efficiency? When it comes to logistics and quality of life in the city, first and foremost, citymakers have choices to make.

This article draws on our report “Stadslogistiek: verkenning van toekomstscenario’s” (“City logistics: an exploration of future scenarios”). We conducted research in spring 2022 with the assistance of TNO (the Netherlands Organisation for Applied Scientific Research) and the City of Rotterdam and financial support from the Creative Industries Fund NL.

[On the pavement...]